Poetry has textures and feeling. And the greats of poetry have lent textures to their words that are felt the moment you hold their compilations in your hand, or read those oft-quoted lines in moments of inner silence. Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s imagery is almost silken, even when he uses difficult and piercing words such as nashtar [lancet]. Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib’s words, on the other hand, are faintly granular, subtle yet abrasive, and layered — as are the ideas behind his words laden with deeper meaning, Farsi derivatives and a timelessness exclusive only to Ghalib. Perhaps this unique texture of his poetry is where Ghalib crosses paths with the texture of the art of Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi.

The work in focus for review is a collection of 47 folders weighing almost five kilogrammes — heavy not just in terms of its physical volume. There is a lot to take in, as it features 43 of the 50 paintings that make up Sadequain’s ‘Ghalib’ series. Titled Ghalib: Call of Angel, this collection was compiled and published as a commemoration of Ghalib’s 150th death anniversary. It has a distinct texture, perhaps by deliberate design of the compilers — the folders are separate and individually complete, yet are bound by thematic cohesion. This allows the reader the choice to pick up one and reflect on it for a day, or days, or pick an irresistible one after the other and turn it into a marathon of reading a choicest selection. The paper is hard and heavy, yet smooth — suited to the texture of Ghalib’s poetry — and solid enough to carry the weight of Sadequain’s artistic renditions.

Compiled and authored by Sibtain Naqvi, the book has been published by Mutbuaat-i-Irfani and this is the sixth book that the publishing house has produced. All six books have centred on the life, times and works of Sadequain. The translation of poetry has been done by none other than the renowned Ghalib translator Dr Sarfaraz K. Niazi.

A compilation of Sadequain’s artistic interpretations of Mirza Ghalib’s poetry delights

The third folio has a sketch of Ghalib’s person by Sadequain, alongside the famous poem Allama Muhammad Iqbal wrote, lauding the prowess of Ghalib. As Iqbal accepts in a line from the poem:

Lutf-i-goyai mein teri humsari mumkin nahin

[Matching you in literary elegance is not possible]

The fourth folio is a brief write-up in Urdu by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, where the inimitable Faiz explains why Sadequain deserves to translate Ghalib into his art, and in the last line gives a testimonial to both Ghalib and Sadequain by saying, “Ghalib ke ashaar ki musawwari Sadequain ke fann ka haqq hai” [An artistic rendition of Ghalib’s poetry is the due right of Sadequain’s art].

This fourth folio is perhaps the only one where a painting of Sadequain is by another artist, Haider Ali.

The fifth and sixth folios include calligraphies of Ghalib’s poetry by Sadequain. It seems Sadequain put his heart into these particular calligraphic renditions, very aware of the power of what he was depicting.

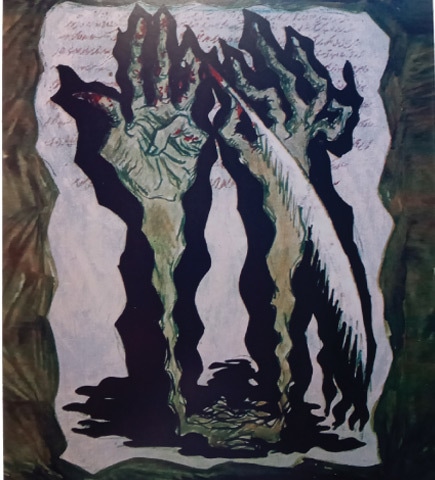

There onwards, it is Sadequain’s artistic depictions of selections from Ghalib’s poetic works. The selections — from both Ghalib’s poetry and the complementing art of Sadequain — are matched so judiciously that it seems like a careful slice from the work of these two has been selected and married in a way so as to give a taste of the many facets of their work. Some of the couplets seem to have touched Sadequain so deeply that they have elicited not one, but two works of art from him, as if the artist felt one was not enough to do justice to it. The compiler and author has dealt with this sensitively and the result is a book that is unmissable by lovers of Ghalib and Sadequain.

In folder 13, the words have the timelessness so typical of Ghalib, where he expresses the dilemma of one trying to walk the tight rope of balancing between love and mundane worldly concerns:

Go main raha raheen-i-sitam-ha-i-rozgar

Lekin tere khayaal se ghaafil nahin raha

[Though I remained involved in managing the tyrannies of living, I was, however, never oblivious of your thought and memory]

Possibly, Faiz was inspired by the sentiment when he wrote “Kuchh ishq kiya kuchh kaam kiya…” [I loved a little and also did some work]. Juxtaposed opposite this verse is an oil-on-canvas painting which Sadequain created in 1969, showing a man bent under the weight of earning a living by carrying heavy wood logs, yet having enough strength to have kept alive an element of romance in him, holding a flower close enough to breathe in its aroma.

Another example of one of the verses where Ghalib wrote about man’s existential condition spanning over the past, present and future is in folio number 27:

Sab kahan, kuchh lala-o-gul mein numayaan ho gaeen

Khaak mein kya sooratein hongi ke pinhaan ho gaeen

[Not all, only a few have become evident as tulips and roses What images may lie in the dirt that remain hidden from us?]

Sadequain, a great in his own right, calls himself “Banda-i-Mirza Asadaullah Khan Ghalib” [follower/servant of Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib] in the 47th folder, the striking and fitting Addendum, where the right-hand side presents a black-and-white photograph of Sadequain showering flowers on the grave of Ghalib alongside Zaheen Naqvi, who was then the secretary of the Ghalib Academy in Delhi. The left-hand side of the folio has what are perhaps scribblings of Sadequain as he calligraphs impromptu some of his favourite lines (not couplets) from Ghalib’s poetry, ending the page with giving himself many self-proclaimed titles, the last two being Baykal and Baychayn, both almost synonyms, meaning uneasy and restless.

Such was the temperament of the works of Sadequain — peace within restlessness, order within chaos, faces defined by his typical sharp, angled strokes, but the overall impact made whole by some softer maestro strokes. This contradiction is perhaps one other similarity between Ghalib and Sadequain, then. While much of Ghalib’s poetry is clearly inspired by the love of the Beloved, he was a man who simultaneously gave in to human temptations — gambling and consumption of alcohol being the most well known. As Naqvi writes in the introduction about him, Ghalib was “equally at ease at the king’s court or the gambler’s den, he was aware of both his poetic genius and his disreputable ways. Rather than put people off, it is this disrepute or badnaami that endears him to the general masses. The man on the street loves a flawed genius.”

The reviewer is a Karachi-based journalist, editor and media trainer; human-centric feature stories and long form write-ups are her niche

Ghalib: Call of Angel

By Sibtain Naqvi

Mutbuaat-i-Irfani, Karachi

ISBN: 978-969792700

188pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, July 5th, 2020

.jpg)