A surge is evident in domestic violence during the pandemic. Experts suggest how this can be countered.

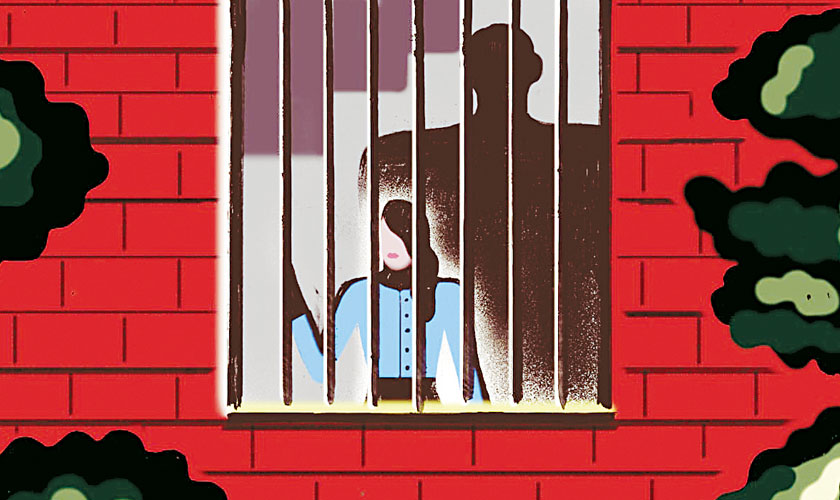

Stuck in your house for months, with minimal or no outside interaction with other humans except via phone or online. The only people you are spending more time with than ever before is your family. Sounds familiar? For some, it may even sound comforting, as home is where one feels safest. But women who are stuck at home with an abusive family member or partner during the pandemic are not safe at home either.

When it comes to the issues humanity is facing due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the loudest voices and most glaring headlines are centered on the public health crisis, crumbling economies, and job loss. What is often ignored, and not fully understood, are the implications of this crisis on vulnerable communities; one of these is women, and one of the problems women are facing more than ever during the pandemic is gender-based violence, in their homes or outside.

Pakistan saw its first two confirmed cases of COVID-19 on 26th February, 2020. In a video message in the month of April, the United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres had warned the world of a ‘horrifying global surge’ in domestic violence during the coronavirus pandemic, saying that “We know lockdowns and quarantines are essential to suppressing Covid-19. But they can trap women with abusive partners.”

As stated in a policy brief by the Ministry for Human Rights, Government of Pakistan, titled “Gendered Impact and Implications of COVID-19 in Pakistan,” evidence suggests that epidemics and stresses involved in coping with the epidemics may increase the risk of domestic abuse and other forms of gender-based violence (GBV). Studies have also found that unemployment tends to increase the risk of depression, aggression and episodes of violent behavior in men. “Hence, the country may experience a rise in cases of domestic abuse as a result of COVID-19. Given the current climate of decreased economic activities, financial uncertainties and a situation of lockdown being faced in Pakistan, heightened tensions could translate into women facing more vulnerabilities,” states the brief.

Why is it happening?

The fears have come true. “There is an increasing global evidence that rates of GBV have increased under lockdown,” says Ayesha Khan, author of ‘The Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Activism, Islam and Democracy’, adding that women stuck at home with abusers who are getting increasingly frustrated by the impact of the pandemic, both economically and psychologically, have nowhere to go.

The psychological factors seem to be the main reason in this rise. “Men as primary earners in many families are feeling the financial pressure and stress more. For many, social distancing has also meant a drastic change in routine because of limited work and socialising, which causes a build-up of stress. For some, the stress is related to constant fear of exposure to COVID-19 because of work or because men tend to do a lot of outdoor work. Sometimes stress manifests as physical symptoms,” says Clinical Psychologist Dr Asha Bedar who has worked in disaster situations, including the COVID-19 crisis. She shares that she has more men presenting issues such as chest pains, breathing trouble and issues sleeping. Men also tend to externalise a lot of their stress through irritability and aggression which can spill into violence at times. The brunt of this pent up stress is faced by the females in the family, mostly the wife.

As Dr Bedar explains, women during the lockdown have had to disproportionately bear a triple burden of work: increased household work with everyone at home, increased and constant caretaking responsibilities (including coronavirus patients), and home schooling of children (including learning and managing new technology). Working women face an additional juggling responsibilities. “Both physical fatigue and mental stress are being reported more. Constant interaction and demands often mean more conflict at home, and can contribute to more depressive symptoms and anxiety. Many women report being left with no time for themselves. Channels for stress relief through breaks, socialising, and other away-from-home activities like office work, shopping, visiting family, socialising with neighbours, friends, or attending classes etc., have also become limited, increasing their levels of stress and anxiety. Irritability, anger, anxiety and depressive symptoms are all emerging more,” she says. This constant friction between stressed spouses means they have less emotional threshold and patience, especially the men. The result is an increase in domestic violence.

According to a UNODC report titled ‘Gender and Pandemic – URGENT CALL FOR ACTION’ advocacy brief, 90% of women in Pakistan have experienced some form of domestic violence, at the hands of their husbands or families. 47% of married women have experienced sexual abuse, particularly domestic rape. Most common forms of abuse, according to the report, are Shouting or yelling (76%), Slapping (52%), Threatening (49%), Pushing (47%), Punching (40%), and Kicking (40%).

“Most Pakistanis have been hit hard socially and economically by the pandemic, but the impact has been different on women and children who have been historically marginalised and prone to be victims of aggression. Covid-19 and its consequences have placed the already vulnerable women in a graver situation due to the triggers for abuse induced by the stress and financial problems coupled with confinement in the home caused by lockdowns,” says Fauzia Viqar, Chief Executive of Rah Centre for Management and Development, a rights advocacy organisation. She confirms that domestic violence has increased and is being reported in larger numbers across the world, including Pakistan. According to her, the recent numbers shared by the helpline of Ministry of Human Rights prove a rise in domestic violence since the lockdowns in Pakistan.

When asked about the reasons leading to this surge, Dr Tabinda Sarosh, Pathfinder’s country director in Pakistan, says that it is due to “lack of mobility and isolation at home, widespread unidentified and unrecognised mental issues combined with pre-existing high incidence of VAWG (violence against women and girls). Global data shows that incidence of DV and VAWG always rises in crises situations and often goes unreported.”

The broader description of violence, according to Dr Shama Dossa, a community development practitioner, researcher and academic, includes psychological violence and deprivation. “The impact of job loss and lack of mobility is more on women. Women are more burdened with household work during the pandemic. The lesser educated the perpetrator, the more the violence,” she says.

According to a UNODC report titled ‘Gender and Pandemic – URGENT CALL FOR ACTION’ advocacy brief, 90% of women in Pakistan have experienced some form of domestic violence, at the hands of their husbands or families. 47% of married women have experienced sexual abuse, particularly domestic rape.

The reporting of DV in Pakistan is not easy because of multiple factors, and women are scared to report due to social taboo. According to the aforementioned UNODC report, only 0.4% of women take their cases to courts. 50% of women who experience domestic violence do not respond in any way and suffer silently. Usually domestic violence is underreported; women stay in abusive and violent marriages till the stage comes when divorce becomes inevitable.

“Generally, help-seeking behaviour is missing. Anecdotally, police officers say that they succeed in convincing the woman to make up and go back home to the husband without registering an FIR,” says Dr Dossa, adding that the reporting process should be set up in a way that women feel more comfortable to report. A big consideration is that if a woman leaves her house after suffering from DV, where is she to go? “In the province of Sindh, there are some functional safe houses at the district level where complainant can stay for a few days.”

Working towards a solution

Experts feel that while the situation is difficult, the way forward for mitigating domestic violence, particularly in the pandemic, requires multi-pronged approaches.

“Domestic violence can be addressed at different levels, such as raising awareness among women and young people, and providing info on coping and safety, as well as setting up and disseminating info on professional crisis helplines with trained counsellors and lawyers. Also to be included in the strategy should be developing SOPs for the police for handling DV especially during COVID-19, setting up safe (including COVID-19 safe) spaces for women and children, strong support from the Government on a no-tolerance approach for violence, creating awareness on anger and stress management for men, and legal awareness,” suggests Dr Bedar.

The support needed is not just logistic and legal, but also emotional, and all these aspects need consideration. Ayesha Khan shares that in Pakistan, civil society groups have helped to set up new helplines to support women needing help from abusive partners, and cites examples. “Rozan has set up a dedicated national helpline under COVID-19 which gives psycho-social support. ShirkatGah is helping the Sindh Commission on the Status of Women prepare a gender response to Covid-19 pandemic, in which GBV and DV are key areas of concern.”

Dr Dossa is of the opinion that the answer lies in a multi-sectoral collaboration which is needed to counter the menace of DV and GBV, which means that the police, the social welfare department, the women’s development department, the population planning department, all work in consortium. As the main systems provider is the Government, this is what is needed.

The aforementioned policy brief informs us that Pakistan’s Federal Ministry of Human Rights has taken an affirmative step through issuing a COVID-19 Alert that provides a helpline 1099 and a WhatsApp number 0333 908 5709 to report cases of domestic violence during the lockdown.

Dr Sarosh feels that healthcare providers like Lady Health Workers (LHWs) or Lady Health Visitors (LHVs) can also be part of the solution “Under ‘NayaQadam’, for the first time in Pakistan, healthcare providers trained on Family Planning are now being trained on GBV services to become first point contacts for the survivors. This would allow women to seek survivor-centred services in full confidential and private settings, receive basic aid, and high-quality referrals to shelter homes, security services, legal recourses, and of course health responses.” NayaQadam is a project led by Pathfinder International with five partners aimed at high-quality FP programming. While this is a feasible solution, the safety of female healthcare providers is also a matter of concern, more so during the pandemic – safety against any kind of violence and exposure to the coronavirus is something that would need to be looked at carefully when they are out in the field or working from makeshift clinics in their homes.

Women have been excluded from most decision making forums on COVID-19, as well as response and relief related groups. According to Fauzia Viqar, National Command and Operation Centre (NCOC) and other high level platforms are cases in point. Absence of the female voice in decision-making for meeting the challenges posed by the pandemic marginalises issues of women, including increase in their care giving role, DV and issues of access to information among others. She adds that COVID-induced restrictions on OPDs and transportation have increased women’s challenges, especially of reproductive health, which is already low in priority. “We need to ensure there is no disruption in services to victims of domestic violence such as helplines, shelters and OPDs,” concludes Viqar.

The writer is a freelance journalist with a focus on human rights, education, health, and literature. She also works as a Communications Practitioner and Media Trainer.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/magazine/you/700989-unsafe-at-home